The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a watershed moment of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Today, nearly 60 years after Rosa Park’s refusal to give up her seat on the bus, the connections between public transportation, social justice and the lives of Black Americans have again come into stark relief here in the Bay Area.

After the appalling deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner attracted national attention last year, Bay Area leaders founded a movement under the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter. Protesters carrying this banner took to the streets all across the nation.

Here in the Bay Area, #BlackLivesMatter protests targeted courts, street corners, freeways and most notably the Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) system. Some have suggested that the focus on BART was misguided. But was it really?

As one report described the events of Black Friday last November:

“A group of 14 people … walked into the West Oakland BART station, hung a banner over the side that read “Black Lives Matter”… The protesters then walked into a BART car headed for San Francisco and locked themselves down to the safety rails inside with cables and bicycle u-locks. Then they locked themselves to each other, forming a human chain that extended out of the car and onto the platform. With the doors blocked, the train couldn’t leave the station. Their goal was to shut down BART for four and a half hours — the length of time that Michael Brown’s body lay in the street. They lasted about an hour and a half; the police ended up disassembling part of the BART car to remove them.”

My friend and UCSD classmate Alicia Garza, a Bay Area resident, co-founder of #BlackLivesMatter, and an organizer for the National Domestic Workers Alliance, led the BART protest. She explainedthat the decision to protest at BART was quite deliberate:

“We decided to find a target relevant to our area. Oscar Grant was murdered at the Fruitvale station on BART – that was one of the first times, in Oakland, that a police officer has been convicted of murder. The West Oakland stop represents a whole different bunch of aspects of state violence against black folks. A thriving black community there was divided and gutted by the development of BART.

BART is a very real representation of how our regional economy functions. BART is what ensures that commuters can get back and forth to SF and San Jose. On Black Friday, BART does something like 400,000 trips a day. It was important to us that the [action] was about stopping business as usual until we get justice for our communities.”

This set of interrelated reasons for protest tracks the reality of BART’s long and troubled history, where urban renewal came at severe cost to the Black community. The part of West Oakland where the BART stop is located, had been a “poor but thriving black community” until construction of “the elevated BART along 7th street, wipe[d] out the main retail stretch along with the jazz clubs” and two major freeways decimated the neighborhood. As Ms. Garza notes, BART is also a public space where violence against Black youth occurs. The #BlackLivesMatter protesters sought to draw attention to the not-so-radical notion that the deaths of black youngsters and the destruction of once vibrant black communities are not wholly separate issues.

Yet, when these protesters’ actions shut down BART for 2 hours, BART police sought $70,000 in restitution from the 14 protesters. Taking a less reactionary position, BART’s General Manager Grace Crunican thought that “the 14 protesters charged with misdemeanor that day should instead perform community service.” BART Director Rebecca Salzman agreed, but when she was later asked via Twitter: “Do you think Rosa Parks should have had to do “community service?” Ms. Salzman replied, “Rosa Parks did not shut down an entire transit system for hours.” She later apologized for the tweet, but stands by her statement on restitution through community service. “We can’t just let people shut down BART all the time.”

In my opinion, civil disobedience is community service. When people volunteer themselves to stand up to injustice, they provide a learning moment for the whole society on the roots and effects of injustice. The 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott was a protest against unfair practices on the public buses and it was a community service to educate Americans on the true plight of the African American. Rosa Parks was part of a well-organized movement that knew that a bus boycott would cause the appropriate important folks to sit up and pay attention. Once the boycott got their attention, they would have the opportunity to either align themselves with the voices of the oppressed, or stand on the wrong side of history. To me, that was a real service to the community as was the BART protest.

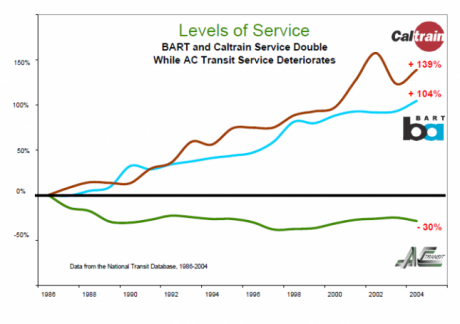

Public Advocates has worked for a long time at the intersection between public transportation and civil rights in the Bay Area, and we know first-hand that the Bay Area is still far from achieving transportation justice. That is nowhere clearer than in African American transit-dependent communities, which face declining bus service and rising fares. Like our segregated bus systems, BART has never been a race-neutral space. As illustrated below, in 2005, BART passengers, who are disproportionately white and affluent, received a per passenger subsidy of $6.14, for each trip. AC Transit riders, 80% people of color and 60% transit dependent, received a public subsidy of only $2.78. As a result, AC Transit bus service was being cut or eliminated, making bus access increasingly unreliable.

Neighborhoods where poor African Americans live are still bearing all the burdens and getting none of the benefits of freeways and rail transport lines that do not serve their needs. For example, in 2009 BART ran afoul of civil rights requirements when it approved the Oakland Airport Connector (“OAC”) without analyzing its impact on low income and minority populations in the Coliseum station area. The OAC does not benefit the area’s overwhelmingly low-income and minority residents due to its prohibitive $12 roundtrip fare and its lack of intermediate stops along the job-rich Hegenberger corridor. BART’s own analysis predicted that less than 3 percent of the OAC riders will come from the immediate East Oakland neighborhoods surrounding the project. In fact, the OAC supplanted affordable AirBART bus service.

The Federal Transit Administration responded to our civil rights complaint by withholding $70 million in federal stimulus funds. Yet even after FTA’s devastating findings, the head of the agency that had allocated the funds — Steve Heminger of the Metropolitan Transportation Commission – explainedwhy that half-billion dollar investment was necessary: the OAC, he said, was “designed with a very special class of transit rider in mind, which is air passengers. Air passengers ride reliability. You pay a premium to get that reliability.”

The implications – that it’s ok to invest huge sums of public money to benefit “special classes” of affluent residents, and that minority and low-income bus riders don’t need reliability in their transit service – continue to make BART’s OAC a poster child for racial injustice.

(Since then, BART has taken several steps to improve its civil rights record, but the structural problems have remained untouched and more needs to be done.)

In short, where people sit on the bus is no longer the burning question. Instead, transportation injustice is now tied to daily necessities like getting to work, to school and to health care. That’s a big reason why public transportation remains an important stage upon which fights for social justice unfold.

Public Advocates stands with the #BlackLivesMatter movement. On January 16, 2015 members of Public Advocates’ staff participated in a “Bay Area Lawyer Die-in” on the steps of the California Supreme Court. We know that business as usual will not lead to the type of change that we need to see. Rather, we need to pay radical attention to the inequities that are shortening the lives and livelihoods of Black Americans. Public Advocates will continue to work diligently for a future where all humans can live and move about with the freedom and dignity they deserve.